It must have been February or March 2018. Procrastinating, I was entertaining myself with planning world domination, i.e., which grants I should apply for. I started toying with the idea of getting funding to organize my dream inductive logic conference. Who would I invite? Some names immediately came to mind, but I quickly realized that I couldn’t really think of many women working in my field – a common problem, I suppose.

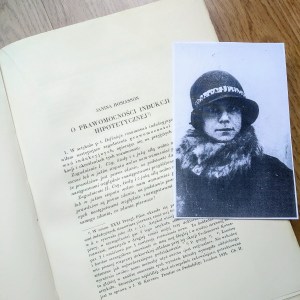

A quick internet search revealed a couple of familiar names, and one new one: Janina Hosiasson. A Polish woman, my age, working exclusively on the logic of inductive reasoning, confirmation, probability. How come had I not known about her before?! I was drawn to her immediately, and wanted to get to know her. There was only one problem: she had died in 1942.

So, I guess no conference invitation from me coming her way. But for some reason, there and then, I decided to find out everything about her. It was not just a philosophical interest; I did not want to only read her work (which – spoiler alert – turned out to be brilliant). I wanted to get to know the person: who she was, how did she end up doing inductive logic, what was it like to be a young woman doing formal philosophy in the 1930s, going to Vienna and all those Unity of Science conferences filled with men in black suits whose wives did all their typing for them. How did she even manage to do research while never having a proper position at the university?

And then, of course, there was the tragic death, of which not much was known. The date 1942 gave the gist of it away immediately. Remember the story, narrated in Tarski’s biography written by the Fefermans, of how the Unity of Science saved Tarski’s life? He left Warsaw for Harvard in August 1939 to attend the congress, and was cut off from coming back home after the war broke out in September – which eventually meant not dying in the Holocaust.

Tarski was not the only Pole scheduled to talk at that conference. Janina Hosiasson was supposed to be there, too. She couldn’t board the boat, for unclear reasons: visa trouble, or a cancellation. Trapped in Europe when the war broke, she ended up in Vilnius, where eventually she was arrested by the Nazis and perished in prison. All of this while continuing to write formal philosophy papers, even while actually in jail (on which more at a later date).

Thus started my search, which has been going on for two years now. It’s been a slow and tedious process, filled mostly with waiting for opportunities to visit archives in various countries. I am trying to put together a coherent story from scraps of material: a handful of letters, written by a person who cared almost exclusively about research; birth certificates and old magazine ads; memoirs of vaguely related people. Many of those scraps are exciting when first seen, even if eventually they will not find their way into the biography. It’s that process that I wanted to document here: the thrills of the search; the quirky finds; getting to know a whole bunch of people from the past and living my life with them.