How much can a few words say?

In February, while on a research trip in Warsaw, I pulled out of the deep vaults of libraries those copies of Hosiasson’s work that actually belonged to her at some point.

Janina Hosiasson-Lindenbaum had a nice habit of writing small dedications on the offprints of her published articles, as she was handing them to other philosophers. Some of those philosophers kept the booklets and in some way or other, the papers eventually made it to the libraries at the university.

In Warsaw, I found nine such offprints with handwritten dedications. (There is also a book which Hosiasson gifted to the philosophy library; I wrote about it HERE.) It is not always straightforward to get these materials: once a digital copy of a journal is available online, the physical copies appear superfluous to institutions and are not even entered into online catalogues. Luckily, they were not discarded! I wonder if there are any copies like this surviving outside of Warsaw, in personal libraries of Reichenbach, Nagel, Carnap?

Of course, those small notes are not an excessively rich source for a historian. But Hosiasson’s Nachlass is not exactly abundant, so we take what we can get and try to run with it.

Ajdukiewicz

One topic I have been interested in recently is the extent of the interaction between Hosiasson-Lindenbaum and Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz. Of the “big males” of the Lvov-Warsaw School, Ajdukiewicz was the one with the most interest in and publications on methodology of natural science, scientific reasoning, inductivism, etc. (I think?) And as such, he was a natural conversation partner for Hosiasson.

She never took courses with him as a student: Ajdukiewicz taught in Warsaw only briefly, right after she had already completed her PhD. In published work, she mentions him in her usual “I saw he did X recently, but I did X earlier and independently” style. Tracing any influences in either direction is subtle work in this case, and bound to be more speculation than fact. In his archive, there is no explicit trace of any interaction between them.

But as it turns out, she did send him her papers, even after he had already left Warsaw. I have found three of them.

“To the esteemed professor Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz by a grateful student Janina Hosiasson (3.III.19[34]).” (There is another copy of this article given to Stanisław Leśniewski and dated 3.III.1934, so I’m assuming the same date here. The booklets were cut to size during binding at the library.)

The “grateful student” part does not feel just like pure courtesy. For instance, she did not write that on Leśniewski’s copy. This makes me wonder whether Hosiasson might have informally attended a seminar that Ajdukiewicz was teaching in the fall of 1927. She was not a student at the time, having received her PhD in December 1926 and not yet having started her subsequent pedagogical studies. But on 19 October 1927 Ajdukiewicz wrote the following in a letter to Twardowski:

Due to the [student] composition of the seminar, I abandoned my original plan to cover the relationship between geometry and experience and instead chose as my topic the question of the justification of induction. (Ze względu na skład seminarjum zrezygnowałem z pierwotnego planu zajmowania się stosunkiem geometrji i doświadczenia a wziąłem natomiast jako temat zagadnienie uprawnienia indukcji.)

Ajdukiewicz to Twardowski, 19.10.1927, LINK TO ARCHIVE

It is not impossible that one of the people attending the seminar was the person who had just written a whole dissertation on the topic.

In 1935, Hosiasson gave Ajdukiewicz her next paper on probability.

To Professor Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz, in appreciation and affection, on 1.VI.35.

And eventually she sent one of her final articles:

To Dear Professor Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz, Janina Lindenbaum 20.V.1941.

In 1941, Hosiasson-Lindenbaum was in Vilnius and Ajdukiewicz was in Lviv. I think she might have visited Lviv during the war, maybe even more than once. Of course mailing things was also possible (to some extent). I was surprised to see that Hosiasson-Lindenbaum received her author offprints of the JSL paper. The contrast between the world that she lived in, and the world where JSL was being published just as it always had been is just so hard to imagine.

Tarski

In the main university library in Warsaw, there are five of Hosiasson’s offprints with handwritten dedications. Three of them were offered to a “dear friend” and two to “dear Freddy” (Fredek in Polish). Given the content of the dedications, their dates, and their numbers in the catalogue (which suggest that they all belonged to one initial collection of materials), I think that Freddy is the dear friend.

Hosiasson and Alfred “Fredek” Tarski were close friends indeed. Up to this point we could only take a peek into the last years of that relationship, when she was writing to him from Lithuania – the only truly personal letters that have survived – and he was trying to get her out of there on an American scholarship. These offprint dedications provide a glimpse into the earlier – happier – years, when they shared a passion for logic, for the Tatra mountains, and – hopefully – also shared some laughs and good times.

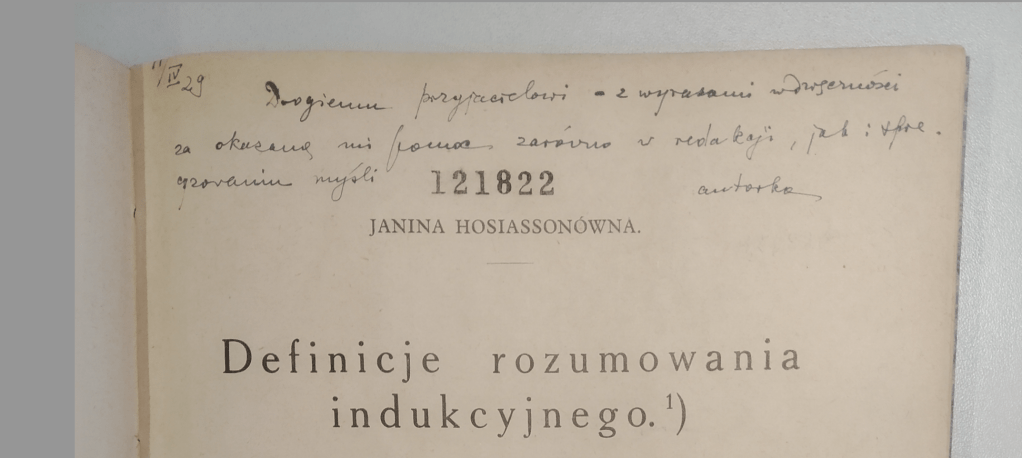

When the first part of her dissertation was finally published as a journal paper, she gave Tarski a copy.

To a dear friend, with gratitude for your help, both in editing and in clarifying my thoughts – the author. [11? 17?] IV 29.

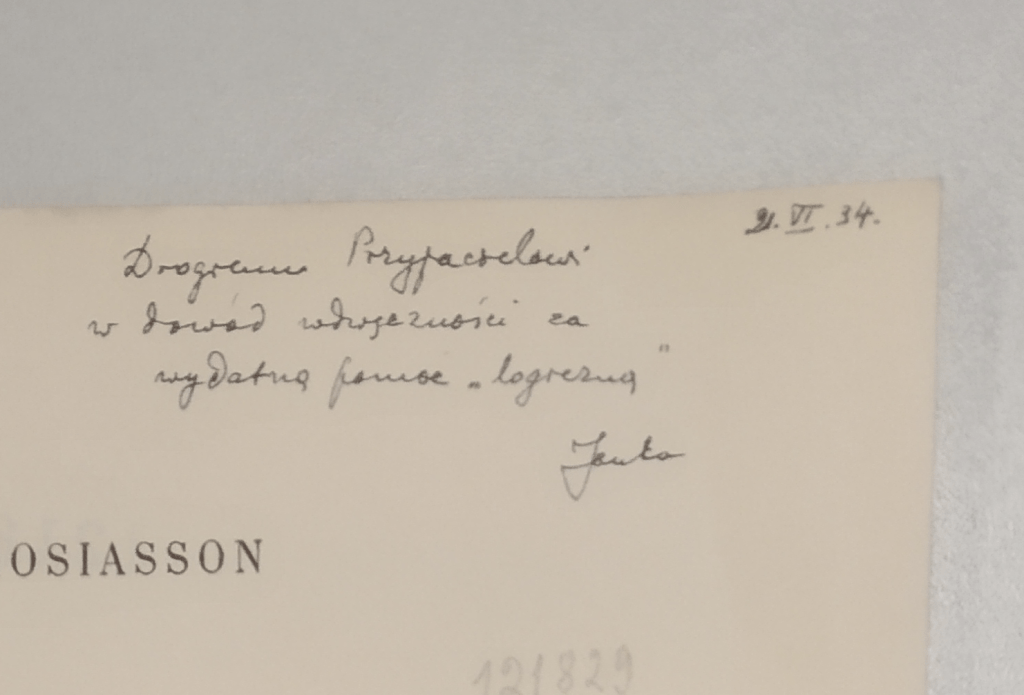

The second part of the thesis was published in 1934, with considerable revisions. The latter included the addition of an axiom system for rational credence functions (which international readers got to see in the 1940 “On Confirmation” article, dressed up as an axiom system for confirmation functions).

To a dear Friend, in gratitude for your considerable “logical” assistance, Janka, 21.VI.34.

In the paper, Hosiasson does actually mention Tarski and some things he had proved within this axiom system, as well as the fact that he had made her aware of some other theorem. But this looks more than just passing some theorems around; it looks like there was an actual community in Warsaw, of like-minded friends who shared their passion for logic and philosophy – and who would not snub anyone, whether a young woman or a Jew (think of Łukasiewicz, whose social and political views did not seem to have influenced his working relationships with other logicians). I wish we could know more about these social aspects of the Warsaw philosophical community at the time.

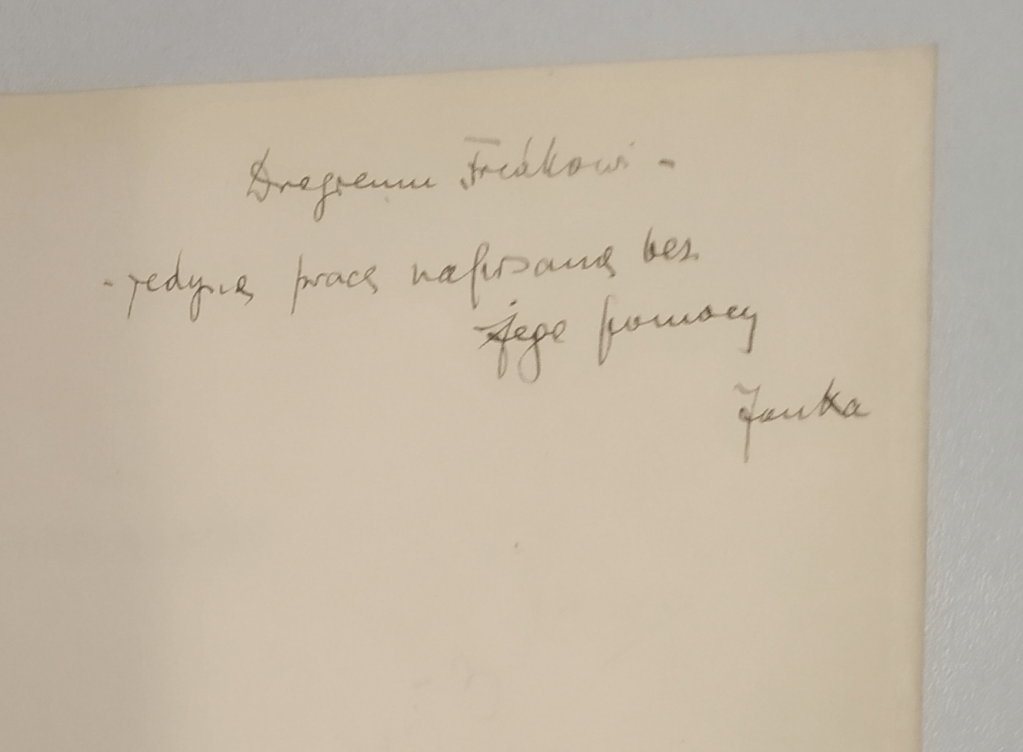

In 1935, Hosiasson published a paper on the psychology of inductive reasoning. It is one of her least formal, mathematical papers: she reports on some experiments she conducted on her high school students, working out the problems associated with Ramsey’s method of eliciting credences from betting behavior. Apparently, in the process of writing it, she did not discuss any of it with Freddy:

To dear Freddy – the only work written without his help, Janka.

I think most people have a friend like this: the logic mastermind, someone who you can always ask about stuff, or who can check your work when you are unsure of it yourself. It must have been pretty fabulous to have Tarski as that friend. (Ok, maybe by “most people” I mean “most logicians”.)

Leśniewski

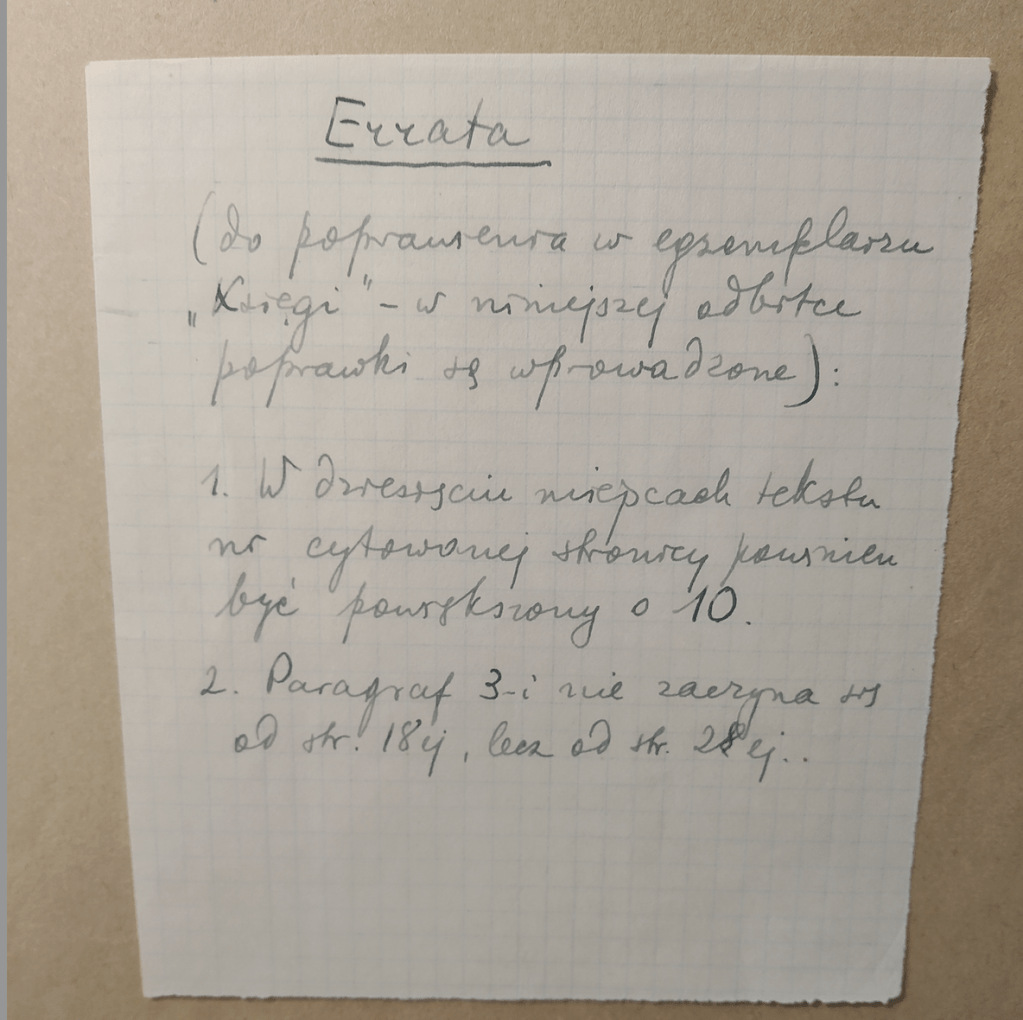

Stanisław Leśniewski’s obsession with exactness and correctness of any formal work is legendary. Add Hosiasson’s own passion for hand-correcting all typos in her articles, and you get this.

Hosiasson dedicated another copy of the 1934 paper to Leśniewski. Although not given by a “grateful student”, it was nevertheless given with “sincere appreciation”. And more importantly, it was gifted together with an insert listing the biggest misprints in the hard copy, so that Leśniewski can apply these corrections in his copy of the whole book (the paper was a chapter in a collected volume of works prepared by Tadeusz Kotarbiński’s students). I am sure he appreciated that.

One of those corrections concerned the place in the paper where the beginning of section 3 should have been placed: it had been placed ten pages too early. Now, normally this is not something we would ever care about ninety years later.

But here’s the thing.

I mentioned above that Hosiasson’s 1934 paper was a heavily modified version of the second part of her PhD thesis. We have no copies of the doctoral thesis to compare this paper with – they were all lost, most likely burned during the Warsaw Uprising. So if we want to know what was in the original thesis and what was added later on, by 1934, we have to do some creative reconstructing, based on the clues she gives us. And in the beginning of the 1934 paper she does mention which of its sections were in the thesis, and which are new: the second section is new, and the third section is old. Hence, where the second section ends and the third begins does matter to our understanding of what Hosiasson was thinking before 1926. Which in turn is important if we want to figure out how much her 1929/1930 stay in Cambridge and the resulting contact with Ramsey’s work changed her approach to inductive reasoning and probability.

Now, here’s for a typo with unexpected consequences!

Dearest Marta, thank you so much for sharing your discoveries!

Best regards,

Janina Hosiasson

LikeLike